CASE STUDY / See all

Words and photography by John Hermans

Bushfire preparation: Wildfire safety

in a bushland setting

John Hermans shares the ways he and his household have set up their house to increase protection of property and livelihood. John first wrote this article for Renew magazine around 2014, and has updated the article in 2021 for the Green Rebuild Toolkit.

After that incredible summer of 2019/20, now regarded as the Black Summer, the entire Eastern States of Australia were subjected to successive runaway wildfire with exceptional loss of natural ecosystems, property, human life and millions of vertebrate mammals, birds and reptiles. The scale of this event was unprecedented in all of Australia’s known human history.

In its 2011 report The Critical Decade, the Climate Commission (now abolished) discussed the link between climate change and increased bushfire risk in a sober and careful manner. “Extreme events that are closely related to temperature are also showing changes consistent with what is expected,” it said. “The intensity and seasonality of large bushfires in south-east Australia appears to be changing, with climate change a possible contributing factor.”

Intense, unseasonal bushfires were certainly the case last year, and the threat will continue. My intention in this article is to share with fellow bush-dwellers the ways my household has set up our property to increase protection and minimise personal risk. Protecting buildings against wildfires is something that we have been working on at our property for the past 30 years.

Increasing a building’s fire resistance

Apart from having a home which is specifically designed and built with wildfire resistance in mind, an uncommon building strategy historically, there is much we can do to increase any building’s fire resistance.

Most buildings are lost due to ember attack, the entry of small burning embersinto areas that start fires which develop and eventually overwhelm the house.

Buildings with a cavity beneath a timber floor need the addition of tough metal fly wire, attached to the peripheral ventilation slats, to minimise the opportunity for embers to enter under the house. A concrete slab on-ground eliminates this problem.

For buildings with cavity roof spaces, combustible debris can build up in and around crevices and gaps, so ember exclusion patching needs to be carried out. Products are available to plug gaps between corrugated iron and sheet metal flashing. Fire-retardant underlay is a necessity under a tiled roof, but debris can build up on top of it, so this needs checking, as does any roofing material prior to each fire season. Roofs with no cavities offer the best protection.

I built my own house with an earth covered roof, however, in order to achieve the best fire resilient home for any given cost, then a simple skillion or gable iron clad roof might be the best option. Using common building techniques allows for cost savings that can then be used to appropriately protect the far more vulnerable doors and windows at ground level where flames and embers are more likely to start a building fire.

Gutters are often a problem area due to the build up of highly combustible leaves. It’s recommended that low combustible facia board is used with gutters to reduce fire risk from leaves. There are now good quality leaf shedding options, to minimise the need to clean gutters regularly. Also consider having a downpipe water stopto allow guttersto fillat critical times.

Windows being broken by either excessive heat or flying objects is another common point of ember and flame entry. Even though toughened glass has more than triple the heat resistance of standardglass, it is safer in high–risk locations to consider placing some form of shutter over the entire window. The type of shutter used is determined mostly by the possible heat load that the window will receive in a wildfire event. Sheet-metal and cement sheet shutters offer a high degree of protection, as long asthey are securely fastenedand emberscan’t find a way around them.

On our house we have also used tightly woven steel mesh and high-temperature fibreglass woven fabric with an outer radiant heat reflective layer, made into simple roll down blinds. The bottom edge of the blind is clamped between two long rectangular sections of flat steel, (20mm x 6mm) to help keep it in place and minimise wind access behind the blind.

Earth bricks or rammed earth offer the highest level of heat-resistance in wall materials. See Renew 110 for a review of the fire-resistance performance of these materials. Regular brick or corrugatediron offers similar protection.

Where timber is used externally on a building, the higher the durability class (density), the less flammable it is, so softwoods should be avoided. On some of the more exposed timbers of our house, I have used spray-on fire retardant. It is easy to apply and not visible. Maintenance is needed as many of these coatings lose their retardant properties over time due to weathering. In high-risk areas, consider not having exposed timber to eliminate this risk or reduce the risk by removing fuel near exposed timber surfaces.

Fuel reduction around buildings

Vegetation close to dwellings should be minimised or removed, unless a suitably sized water sprinkler system is in place to keep that vegetation wet, or you have low flammability plants. Reducing the amount of fine fuel (less than 6 mm stem diameter) will reduce the likelihood of fire spreading through your property.

The crowns of large trees, even eucalypts, when spaced apart and with a managed understorey are far less likely to carry a crown fire, andcan assist in reducing wind loading on your house during fire events. They also act as undergrowth vegetation suppressors, and wind deflectors. I believe that too many trees are removed in the name of fire safety, when it is the lower-growing vegetation that creates the greater flame and heat threat. An expression commonly used is ‘spaced trees are safe trees’.

Keeping the building perimeter clear of combustibles is an important fire-preparation job. Things like firewood, door mats, chairs and windblown dry leaves and grass need removing. Leaves and grass against buildings and fences will create a weak link.

We use a vegetation shredder in areas near to the house, with this pulverised material used to make compost forour vegetable garden. For areas over 30 metres away we carry out small mosaic burns, or rake and burn in piles; check with your fire authority prior to doing this. Using a trailer to cart dead organic matter away is another strategy that is highly effective, right through the summer season.

Water saturation around buildings

A good proportion of households in forested areas have a water supply and fire-fighting hoses.This basic setup is far from adequate in many cases. Many water-based homefire-fighting setups fail for a variety of reasons including insufficient water to adequately protect life and property. Failure of the motor which drives the pump, ineffective water distribution, or the fire being beyond the capability of people to defend, are outcomes to be avoided.

Mains water supply is often overdrawn during fires so it is too risky to rely on. If you are planning to stay and defend your home, then you need assurance that sufficient water is available for fighting fires when needed. As the most disastrous fires have come after the end of a long dry period, household water supplies are usually very low when a fire is on its way. Dedicated fire-fighting water tanks should be considered, and kept full for this purpose. Short test runs with all sprinklers going anda fire hose, needs to be carried out to test for both pressure drop and give an indication of the run time of the water supply volume.

Grid dependent electric pumps are not a reliable option, as blackouts are the norm in a fire. Petrol or diesel-powered pumps need to be started weekly to give some confidence that they will start when really needed. Ensure that it is regularly maintained and has a cover to prevent mud fouling the exhaust and protect the pump from radiant heat. Petrol pumps fail when excessive air temperature vaporises its fuel. I experienced this personally during a bushfire at my property in 2020. The most effective water-pressure system is derived by having a water-supply tank, up on a hill, preferably with over 10 metres head. This means you will always have pressure as the pumping has already been done.

On our property we have a concrete tank that is mostly earth bermed, with a volume of 220,000 litres. It delivers water to our living zone through a 100 mm PVC pipe buried to 40 cm, allowing for over 50 sprinklers to be run with minimal pressure drop. This may sound excessive, but it is designed to defend a rainforest gardenvery nearto the house. This potential weak link (thick vegetation close to the house) had little chance to burn during the 2020 bushfire with the distribution of water sprinklers inside the leafy rainforest. There was a six-hour period of burning native forest all around us, but in this wetted rainforest zone the frogs were singing, as they thought it was raining! It’sabout providing the resources to suit the conditions.

Being able to direct water quickly and effectively is what counts. If an adequate water supply is availablethen surrounding structures with sprinklers inhibits the ignition of buildings and gardens in the first place. If enough sprinklers are set up, then the need for running around with hand-held hoses in a dangerous environment is significantly reduced. This wasso evident in the real eventthat we experienced.

There are a couple of things to noteon the use of sprinklers: The delivery rate of water to the combustible vegetation or buildings needs to be greater than the evaporation rate.Theseconditions are more severe than you will ever be able to test in.Regardless of this, try test running all sprinklers at once, on hot, dry, windy days. When a fire is close, the volume of water that needs to be released is high, and in order toavoid excessive pressure drop and hence a reduced flow from sprinklers and fire hoses, the size of the distribution pipes needs to be sufficiently large. Be aware that excessive heat may burst exposed plastic pipes or sprinkler risers, leading to gushing leaks and system failure. Above-ground pipes need to be steel or copper; PVC and poly pipes need a minimum soil cover of 30 cm. Underground pipes will not melt when water is flowing through them.

The placement of sprinklers on steel roofs can bewastedeffort and water, unless they are protecting combustible building components, such as timber clad walls on stepped roofs or clearstory windows. Steel roofs do not burn. Concentrate your efforts on wetting down surfaces that can combust or that are weak points such as doors.

Having exposed plastic water storage tanks is an issue that is often overlooked. Even when full, plastic tanks can soften and burst when exposed to enough heat. They can be shielded with a barrier of corrugated iron.

Our living zone had two 14 metre long, three-metre high rammed earth walls, to divert wind, embers and radiant heat away from the open–fronted workshop and the most vulnerable edge of my rainforest plot. Where wind speeds are significantly reduced, fire suppression is eased, and sprinklers can be smaller.

[Ed: The use of sprinklers and their location is complex and advice should be sought from your local rural fire service.

Fighting fires

Given the measures we have in place, our fire plan involves staying to defend our home. However, fighting wildfires can be very dangerousand people planning to defend their own homes must take this fact seriously. They must be in good physical condition and must have a place to take shelter if the situation gets beyond their control, including fallback options. Suitable footwear, clothing, breathingand eye protection need to be kept in a box along with a written fire plan and functional torches.

The decision to evacuate or to stay and defend your property against a wildfire must be made based on the forecast weather conditions leading up to a fire and the decisions in your fire plan. If evacuation is required, allow plenty of time to reach safety. Many people who die in wildfires are trying to evacuate too late.

This article only gives a brief outline of our preparations and people will need to research further to protect themselves and their properties effectively.

Fire plan

A written fire plan adds significantly to personal and house protection. For those situations where you choose to evacuate, it can simply be a list of things to take with you and when to leave. On ‘code red’ days, it should be with sufficient time to get to an area unlikely to be affected by fires and certainly before a fire starts; on less severe days, evacuation might be initiated by news of a fire in your area. For those who intend to stay and defend, depending on the severity of the fire, the plan needs to be far more detailed. The stay-and-defend choice is more likely to lead to some level of panic and a plan on paper gives clarity to the actions to be carried out. A plan can also be used annually to remind household members of the fire-preparation process. Ours was written in large print and stapled to a wall in an easily accessed workshop. An inexpensive set of walkie talkies were also used to add personal safety. We had a crew of five family members defending our property in 2020.

Bunkers

If considering a fire bunker, seek advice on their design and location, as seven people died in bunkers in the Black Saturday fires. They must be away from other buildings.One useful reference is: Performance Standard for Private Bushfire Shelters from Australian Building Codes Board www.abcb.gov.au

Be prepared, but be cautious

There are no guarantees that a building or lives can be protected from a wildfire. In the Black Saturday fires, many people died in their homes, and, according to the Royal Commission, about 20per centof those who died would have been consideredwell prepared. Remember, a house can be replaced, lives cannot. The safest option is to leave early. Seek advice prior to the start of the fire season and prepare your fire plan. Irrespectiveof all ofthe above, ‘prepare your property’. Even small clean up tasks done shortly before a fire comes through your property can mean the difference between a total loss outcome or no ignition, meaning you get to keep your hard-earned lifestyle.

Clerestory window blind end-joiner. Wind is the nemesis of lightweight materials. Here I am attaching a plate of aluminium to join the two blind edges together, clamping them against the window frame to keep out wind and embers.

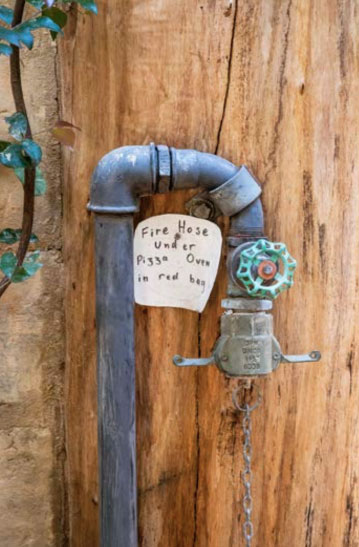

Valve assembly for a fire hose. Standpipes for fire hoses need to be suitably sized, and hoses easy to find.

John Hermansis a regular contributor to Renew magazine. His primary interests are in low emission technologies along with local ecological sustainability. He holds a BSc in Forest Ecology.

You can read about John Hermans’ sustainable homeand experience during the 2020bushfires in this article by Nilmini De Silva on the Medium website.